By: Elizabeth McGuire

There are many reasons a rising star professional might join a leadership development program: to build skills, expand her network, connect with the community. Saving a life is not usually one of them.

But that is exactly what happened when two women met through Leadership Austin’s Essential Class of 2016. Lydia Clay, a project manager with Momark Development, applied to the program hoping to find a new community and a deeper understanding of the city. “What I got was so much more,” she said.

Emily Chenevert, Director of Operations with Austin Board of REALTORS®, applied to the program at the encouragement of her boss. At the time she had just received a promotion and was a well-known name in real estate circles, both for her work ethic and her engaging personality. (Lydia would later describe Austin’s real estate world as “Two degrees from Emily.”)

EMILY

Emily’s work life was full-throttle, but her home life was even more so. When she applied to the program, she and her husband, Hunter Chenevert, had two sons: 4-year-old Hudson and 6-month-old Barrett. In the early weeks of Emily’s pregnancy with Barrett, they learned that he had posterior urethral valve obstruction, which meant his ill-formed urethra would inevitably harm his kidneys and dramatically impact development of other organs, including the lungs. Barrett would be on dialysis immediately and for the rest of his life—unless a kidney donor was found.

Doctors immediately began administering ambitious, in utero treatments to decrease the damage on the growing baby. Emily was hospitalized for the last six weeks of her pregnancy and on December 9, 2014, Barrett Wells Chenevert was born at St. David’s North Austin Medical Center. When Barrett (“Bear” as his family calls him) was two days old, he was transferred to Dell Children’s Hospital. On Day Four, doctors operated to insert a tiny catheter for administering his daily dialysis treatment.

Once Barrett arrived home, daily life began, and it looked something like this:

Juggle the demands of a preschooler and a newborn; Make regular trips from home in Pflugerville to Dell Children’s; Manage insurance and appointments and mountains of paperwork; Administer daily dialysis treatments; Keep Barrett germ-free to avoid infections at his insertion site; Balance work and marriage; Fight to stay positive.

When Barrett was 13 months old, he was large enough and healthy enough to be put on the donor list at University Transplant Center in San Antonio. “Neither Hunter nor I were a good match,” said Emily. “Other family members had tried and so did a colleague.” Live donors are rare outside of family members, so they assumed a deceased donor would be their best option.

Their family life became one long, tedious waiting game. It was during this intense time that Emily was accepted into the Essential program. Emily admits the program became a healthy distraction from the stress at home—an opportunity to “not think about myself for a while.”

LYDIA

Meanwhile, Lydia had been building her career as a make-it-happen professional. She specialized in community building and economic development, serving as Chief of Staff for a former two-term Houston City Council Member. In 2011 she returned to her native Austin and eventually began working for Momark Development, overseeing a portfolio of real estate development and construction projects ranging from luxury condos to affordable housing.

When she learned she had been accepted into the Essential program, Lydia was excited and honored, and also a bit surprised. “Essential is comprised of individuals at the top of their career and industry,” she said. “I felt out of place at 30. I figured I’d start applying early in hopes of being accepted after a few rounds of application. Once in the class I came to see my value and see that I belonged.”

KINDRED SPIRITS

When Emily and Lydia describe their first few encounters they talk of various missed connections. Though they both worked in real estate, had attended many of the same events and shared mutual friends, they had never met. In December 2015 they found themselves seated next to each other at an Essential class and quickly bonded thanks to their “super wonky and policy driven” interests. “Clearly we were real estate sisters,” said Lydia. “It’s really sad when you bond over land development code.”

It would be another four months before Emily and Lydia connected again, this time at a class discussing community health care. Their conversation turned to Barrett and the nature of waiting on a transplant list. To Emily’s surprise, Lydia knew exactly what she was going through. Lydia’s father had passed away nine years earlier after waiting for a liver transplant for almost six years. The years of illness and waiting had been a formative experience for Lydia, and she now realizes that she was still grieving and processing the pain and loss long after he died.

It would be another four months before Emily and Lydia connected again, this time at a class discussing community health care. Their conversation turned to Barrett and the nature of waiting on a transplant list. To Emily’s surprise, Lydia knew exactly what she was going through. Lydia’s father had passed away nine years earlier after waiting for a liver transplant for almost six years. The years of illness and waiting had been a formative experience for Lydia, and she now realizes that she was still grieving and processing the pain and loss long after he died.

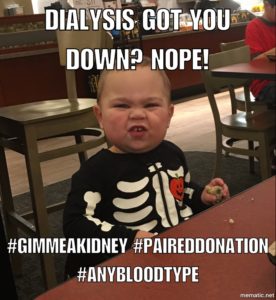

From then on, Lydia closely followed Emily’s Facebook updates about Barrett. “I thought about Bear often over the next couple months, and then there was one post that really struck me,” said Lydia. Emily remembers it well: “He had been on the list for 13 weeks and I had just hit my wall. I was so depressed and feeling so raw about his wait.” She decided to make a direct appeal to her friends, using the power of cuteness. She whipped up a Bear Meme: taking a photo of 18-month-old Bear making his signature “scrunch face” along with this message: “Dialysis Got You Down? Nope! #gimmeakidney #paireddonation #anybloodtype”

Lydia saw it and immediately knew that 13 weeks was a long time on the kidney list for a baby. She decided right then to get tested.

“I remember going home and telling my girlfriend, Cory. I give her tremendous credit because not a lot of people would be supportive when you say, ‘I’m going to get tested to donate a kidney to a child I haven’t even met. I think I want to do this.’”

TESTING

The entire donor compatibility process took a month and included rigorous health screenings plus two long days of testing and interviews. Lydia left the experience with renewed respect for the transplant team at San Antonio’s University Transplant Center.

“The last round of testing is the most intense. It was physically grueling and mentally exhausting. The day includes a 24-hour fast: no water or food, a CAT scan, MRI, multiple blood draws, an EKG and a number of other tests. Intermixed with these tests are a series of focused interviews with nephrologists, the transplant surgery team, your assigned social worker, a medical ethicist and a donor coordinator. To be approved as a donor you must also have an approved caretaker for the full duration of the surgery and recovery. So while I was undergoing the medical tests, Cory was interviewed and screened as my caretaker. You have to prove you can financially do all this, which is great…they are really trying to make sure it doesn’t harm any party.”

The result? Lydia was not just an acceptable candidate, but a perfect 10 out of 10. The staff told her they never give out ratings this high.

Even with her perfect score in hand, Lydia still didn’t know if she was a match for Barrett. At this point she had to decide if she would donate only to Barrett, or if she were willing to donate to a stranger via a “paired donation.” This type of donation connects two donors with two recipients when incompatibility is an issue. By exchanging donors, a compatible match for both recipients can be found.

“The idea of a paired donation was a difficult ethical dilemma,” said Lydia. “I kept thinking, ‘How do I know if a total stranger will take care of the kidney? I finally decided that I couldn’t be the judge of who is more or less deserving of a new life. Ultimately it was reflecting on my father’s experience that solidified my choice to agree to a paired or direct donation to Bear. I would have loved for someone to have done this for my Dad.”

Lydia credits the transplant team for framing the conversation in a beautiful, human way. “If you have cancer you can walk in and get treatment, and nobody is really precluded from that,” she said. “But with this, it’s a lottery. It’s who’s lucky enough to even get the chance at a transplant. In the U.S. there are 130,000 people waiting for a lottery. What other illness do you know of where that’s the solution? Just sheer luck.”

At this point, Emily and Lydia finally exchanged phone numbers. “We had only been communicating on Facebook Messenger,” said Emily. “That’s how much we didn’t know each other.”

At this point, Emily and Lydia finally exchanged phone numbers. “We had only been communicating on Facebook Messenger,” said Emily. “That’s how much we didn’t know each other.”

Both agreed a little distance during that time was important. “We were friendly and we talked, but didn’t exchange a lot of important information,” said Lydia. “I wanted to make sure I was fully ready to do it and fully approved before any hopes were built.”

Good news arrived on an ordinary October day. Lydia was a match with Barrett. Emily was working at a trade show when she got the call. “I was shocked,” she said. “All along I had been waiting for the other shoe to drop. You start to protect yourself—I didn’t think it could happen.”

The surgery was scheduled for a month later, and Lydia calls the timing “a miracle and divine intervention by the universe.”

“I remember telling the transplant team that my life would be crazy in January and the only time my business dies down is November and December. My company is incredibly supportive…but it would have been very difficult to take 6 to 8 weeks off during any other time. l was also coordinating with Cory’s schedule, and holidays are her only slow time.”

The two families met for the first time at Torchy’s Tacos and hit it off immediately.

“We kept thinking, this is really wild,” Lydia said. “We don’t really know each other and we’re about to go through this incredibly intimate process…exchanging lives and body parts and all this.”

“I remember that you asked Hunter and I how Bear’s life would change,” said Emily. “And without skipping a beat I said, ‘In every possible way.’ I believed it then, but now I know it.”

SURGERY

When the big day arrived on November 17, 2016, the plan was to remove only one of Barrett’s native kidneys and to add Lydia’s, but once doctors began operating they saw that both kidneys were too damaged to remain. Barrett’s 8 hours of surgery turned into 11 hours.

In another operating room, doctors spent four hours working on Lydia. “The survey is a difficult one. During kidney harvesting every major abdominal organ is moved, some even temporally removed from your body, to ensure the kidney is easily accessible and safely removed.”

Lydia was in the hospital for 6 days, home from work for 4 weeks, working part-time for another 3 weeks, and not 100 percent for 8 to 10 weeks. To her chagrin, Barrett recovered much faster, and was running circles around her after just a few weeks.

An infection prolonged Lydia’s recovery, but she had tremendous help from her partner, Cory. “She is the unsung hero in all of this and has the biggest heart. No one in my family had the ability to take off a month of work. She was a tireless caretaker and provided endless emotional support. I love her more than ever.”

GIFTS

Four months after the surgery, with life leaning toward a new normal, Emily and Lydia reflected on the countless rewards from their shared experience.

A huge weight has been lifted. “Everything about that child is different,” said Emily. “They tell you to expect it, but you can’t know it until it you’re there.”

That said, Bear will always live with risks. “He still has labs regularly, and we’re constantly looking out for those infections that could hurt his kidney, and he’s more susceptible to cancer. But while he is healthy…we refuse to live in fear. There’s a fear that we just put on a shelf.”

“We recently went on a date without kids. Two weekends in a row! It was mind blowing. We have been so wrapped up for two years just trying to survive. Both kids have been to hell and back, so the idea that we could be thriving as a family…it’s freeing.”

“People ask how you thank someone,” Emily said. “I’m pretty good with words but I don’t have those words. The only thing we can ever do to thank Lydia is to give Barrett and Lydia the opportunity to share their own relationship and develop that the way they see fit. The only gift we can give is to be out of the way when he’s old enough to be nice and respectful.” She laughs, “He’s two…he’s not always nice!”

“Every day I think about him, and I think about Emily and their family,” Lydia said.

“I don’t have kids but I have a niece and a nephew who I love dearly…but I think this experience is the closest thing I’ll ever have to motherhood. It’s hard to describe what it feels like to have a piece of you inside someone else—you’re worrying about them and hoping for them to just have it easy.”

“I just want him to wear a seat-belt when he’s 16,” Lydia said. “I want him to be protected. It’s a change to think beyond, ‘Oh let’s go have fun and I’m going to spoil you with candy’…but to actually have those maternal instincts of wanting him to be OK. Seeing him after the transplant, my first thought was: I want him to have everything.”

The surgery not only gave Lydia a new perspective, but changed her on a profound level. “I feel emotionally and physically strong in a way I’ve never felt before,” she said.

“I can’t imagine what my life would be like had I not donated to Barrett.” Lydia said. “The experience has had a profound impact on my life. I have a new sense of purpose and fearless approach to life. I’m not afraid of anything now. I think that is what the experience has taught me: knowing you’re taking a huge risk, weighing it and saying. ‘The outcome of truly living life is more important.’ That annihilates fear and opens a world of new possibilities. ”

ONWARD

No surprise, Emily and Lydia are both effusive advocates for the organization that initially brought them together. Although Emily jokes that “blood type” should be added to the application form for Essential, she sincerely calls Leadership Austin a hero in this story.

“What Leadership Austin does really right is to form very authentic, very genuine and deep relationships from Day One,” she said. “Before Lydia even did this for our family, I knew that she was a person capable of this kind of compassion. And I would not know that about people who I just meet randomly in business.”

Emily and Lydia didn’t join Leadership Austin to save a life, but to hear them tell it, the decision actually saved more than one.

###

On June 2, 2017, Lydia Clay will be honored with Leadership Austin’s Ascendant Award, which is given to a recent graduate who has demonstrated community leadership in a manner than exhibits the honoree’s commitment to the core values of Leadership Austin: Community Trusteeship, Inclusiveness, Collaborative Decision-Making, and Personal Responsibility. For more information, visit leadershipaustin.org.